CASE REPORT | https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10057-0107 |

A Case Report of Hydrops Fetalis with Cystic Hygroma

1–4Department of Radiodiagnosis, Mahatma Gandhi Medical College and Hospital, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India

Corresponding Author: Piyush Kumar Agarwal, Department of Radiodiagnosis, Mahatma Gandhi Medical College and Hospital, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India, Phone: +91 9462807926, e-mail: piyushagarwal330@gmail.com

How to cite this article Agarwal PK, Rahi S, Baberwal MC, et al. A Case Report of Hydrops Fetalis with Cystic Hygroma. J Mahatma Gandhi Univ Med Sci Tech 2019;4(2):44–45.

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

ABSTRACT

Hydrops fetalis is a condition of accumulation of extracellular fluid in the body cavities. Depending on its severity, there could be involvement of fetal serous spaces, skin, placenta, and other organs. Hydrops fetalis can be of two types: immune or nonimmune. Immune hydrops fetalis is most commonly caused by erythroblastosis fetalis due to Rh isoimmunization. Nonimmune hydrops fetalis is caused by cystic hygroma, parvo virus infection, TORCH infections, congenital heart block, and structural and congenital anomalies. In earlier days, hydrops was most commonly due to Rh isoimmunization, but nowdays, with the use of Rh Immunoglobulin (Anti-D), most cases of hydrops are due to nonimmune causes. This is a case of a female with 18 weeks pregnancy with hydrops fetalis and its association with cystic hygroma and other chromosomal abnormalities.

Keywords: Cystic hygroma, Erythroblastosis, Hydrops fetalis, Nonimmune hydrops.

INTRODUCTION

Ballantyne first described hydrops fetalis in 1892.1 Hydrops fetalis is the Latin word for edema of the fetus. Hydrops fetalis is an end-stage process for many diseases. It is a condition in which there is an accumulation of interstitial fluid in at least two body cavities (pleural, peritoneal, or pericardial) or one body cavity in association with anasarca.

Other features include fluid accumulation in soft tissue with thickness more than 5 mm. In addition, sometimes, it is also commonly seen with polyhydramnios and a thickened placenta more than 6 cm in 30–75% of patients. Some hydrops fetuses also have hepatosplenomegaly.2

CASE HISTORY

A 23-year-old female, G2 P1 L1, presented to us for normal routine antenatal checkup. Her LMP was 8/09/2016.

There was no history of diabetes and hypertension. She had Rh+ve blood group and had nonconsanguineous marriage. Gestational age of the fetus was determined by fetal biometry parameters, such as biparietal diameter, head circumference, and femur length, and it was found to be corresponding with the menstrual history of the patient.

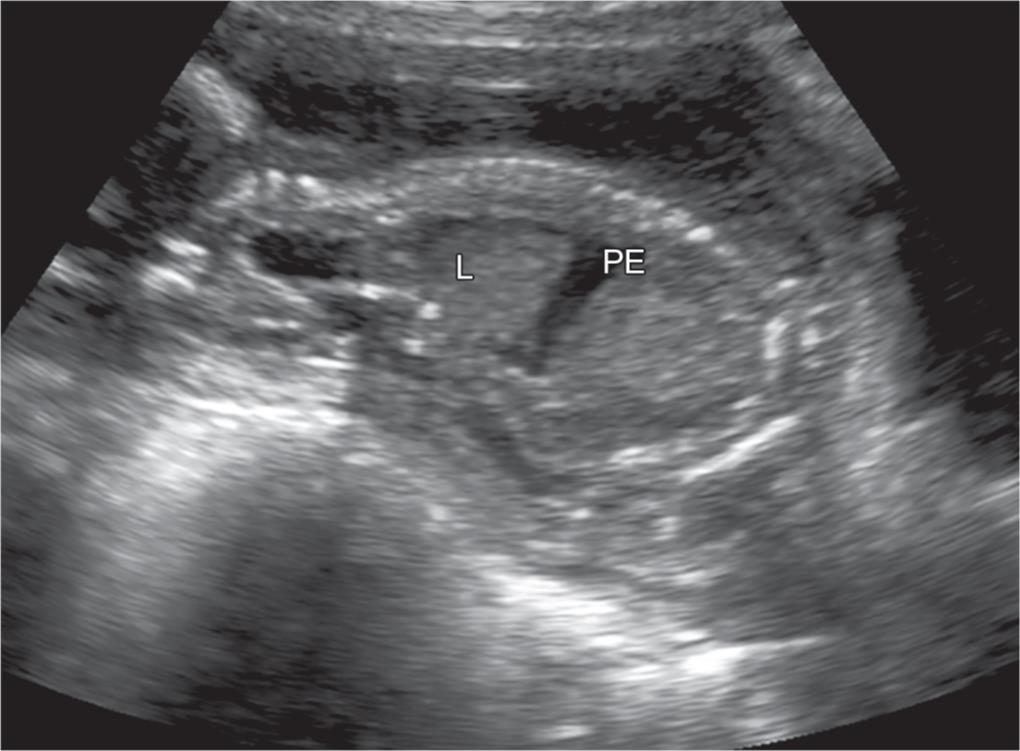

Ultrasonography was done to find congenital anomalies, and it stated that a single live intrauterine pregnancy of 18 weeks and 1 day with cystic hygroma seen at the posterior aspect of the neck, massive skin edema, bilateral pleural effusion, and echogenic foci in right ventricle (Figs 1 to 4).

DISCUSSION

Hydrops fetalis refers to fluid accumulation in serous cavities and/or edema of soft tissues in the fetus. The incidence is approximately 1 in 2,500 to 1 in 3,500 neonates.3

The basic etiology of hydrops is an imbalance of interstitial fluid, which may be caused by myocardial failure, high-output cardiac failure, decreased colloid oncotic plasma pressure (anemia), increased capillary permeability, and/or obstruction of venous and lymphatic flow. In short, there are at least 80 different known causes of fetal hydrops. The two broad categories of pathologies include those of an immune origin and those of a nonimmune origin.4 One of these nonimmune causes includes cystic hygroma. Cystic hygroma is a localized single or loculated fluid-filled cavity that usually occurs in neck. It is believed to develop secondary to congenital blockage of the lymphatic drainage.5 It is seen in over one-third of fetuses with nonimmune fetal hydrops6 and have high association with Turner syndrome and Trisomy syndrome 13, 18, and 21.

Fig. 1: Ultrasound image showing well-defined anechoic asymmetric multiseptate thin-walled cystic mass seen at the posterior aspect of neck of the fetus

Fig. 2: Image showing fetal head with subcutaneous edema

Fig. 3: Ultrasound image showing marked fetal subcutaneous edema. Note the callipers for estimation of gestational age; however, subcutaneous tissue is to be included for correct estimation of fetal weight

Fig. 4: Sagittal image of the fetus showing fetal lung and pleural effusion

Cystic hygroma is one of the possible causes of hydrops fetalis. It is the most common form of lymphangioma, and it consists of hugely dilated cystic lymphatic spaces. Seventy-five percent of these malformations occur in the neck, particularly within the posterior compartment, and up to 10% of these nuchal hygromas may extend into the mediastinum. Twenty percent of hygromas are found in the axilla. More rare locations include the retroperitoneum, abdominal viscera, and groin. These malformations tend to occur in or near the location of the primordial lymphatic sacs from which they arise, i.e. jugular, axillary, and internal thoracic.

At ultrasonography, whenever cystic hygroma is found, one should do amniocentesis. Cystic hygroma is commonly seen with cytogenetic abnormalities as high as 73%.7

Trisomy 21, 18, and 13 are more common in fetuses with cystic hygroma in the first trimester. Turner’s syndrome is more common in fetuses with cystic hygroma during second trimester. Almost all fetuses with hydrops associated with cystic hygroma die antenatally. Cystic hygromas without hydrops usually regress fully. Ultrasound monitoring is required every 3–4 weeks, and genetic counseling is done.

CONCLUSION

There is an association between cystic hygroma and hydrops fetalis, and genetic evaluation of the fetus and parents is needed to establish or exclude aneuploidy.

REFERENCES

1. Abrams ME, Meredith KS, Kinnard P, et al. Hydrops fetalis: a retrospective review of cases reported to a large national database and identification of risk factors associated with death. Pediatrics 2007;120(1):84–89. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2006-3680.

2. Has R. Non-immune hydrops fetalis in the first trimester: a reviewof 30 cases. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 2001;28(3):187–190.

3. Bijma HH, Schoonderwaldt EM, van der Heide A, et al. Ultrasound diagnosis of fetal anomalies: an analysis of perinatal management of 318 consecutive pregnancies in a multidisciplinary setting. Prenat Diagn 2004;24(11):890–895. DOI: 10.1002/pd.883.

4. Randenberg AL. Nonimmune hydrops fetalis part II: does etiologyinfluence mortality? Neonatal Netw 2010;29(6):367–380. DOI: 10.1891/0730-0832.29.6.367.

5. Callen PW. Ultrasonography in obstetrics and gynecology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1994.

6. Santolaya J, Alley D, Jaffe R, et al. Antenatal classification of hydrops fetalis. Obstet Gynecol 1992;79(2):256–259.

7. Shulman LP, Emerson DS, Felker RE, et al. High frequency of cytogenic abnormalities in fetuses with cystic hygroma diagnosed in the first trimester. Obstet Gynecol 1992;80(1):80–82.

________________________

© The Author(s). 2019 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and non-commercial reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.